Poverty and Policy: A Timeline of Discrimination and Missed Opportunities

October 2, 2020Discrimination, often government sanctioned, prevented Blacks for pursuing homeownership, education, loans and good-paying jobs, much of which persisted legally well into the 1960s. As whites accumulated generational wealth and left the cities to the government-funded suburbs, Blacks were trapped in overpopulated poorly funded urban neighborhoods constrained by discriminatory policy and societal framework that prevented their social mobility and entrenched many in generational poverty.

These inequities perpetuated the economic inequalities at the heart of today’s social justice movement and the racism it seeks to end.

Click here to view entire timeline.

1920s

The Black population in Detroit swelled from 41,000 to 120,000 as new migrants from the South arrived daily to seek employment in the auto industry. The cramped near east side neighborhood of Black Bottom was one of the very few areas blacks were allowed to reside.

1924

National Association of Real Estate Boards created a rule to revoke the license of any broker who introduced someone of “the opposite” race into a racially homogenous neighborhood.2

1925

Prominent African American physician and Detroiter Ossian Sweet tried and acquitted for murder after shooting into a crowd of several hundred angry white people surrounding his newly purchased home in a white neighborhood.5

1933

Half of the mortgages in the U.S. in foreclosure due to Great Depression. This spurred government action intended to increase homeownership. These efforts favored whites over Blacks continuing the racist policies of the real estate industry and leading to decades of disinvestment and underdevelopment in cities where Blacks lived.2

1934

Federal Housing Administration created to boost economy and number of homeowners. FHA guidelines create redlining zones of Black and minority communities where the federal government will not guarantee loans.3 From 1934 to 1962, 98% of FHA-backed loans went to white homeowners. In total, of the $120 billion of new housing subsidized, less than 2% went to non-whites.5

1944

G.I. Bill passes providing benefits such as low-interest mortgages and tuition stipends. While it extended benefits regardless of gender or race, Blacks and women struggled to receive higher education or loans like their white counterparts.

1947

Of 545,000 housing units available in the Detroit area, only 47,000 were available to Blacks. In fact, between 1940 and 1947, every subdivision developed specified the exclusion of Blacks.5

1948

Supreme Court finds enforcement of race-specific covenants barring home sales to nonwhites illegal in Shelley v. Kraemer.5

1951

55.5% of job orders placed with the Michigan Employment Security Commission “were closed” to non-whites by written specifications. In one month of an acute labor shortage, Michigan State Employment Service’s Detroit office reported 508 unskilled jobs, 423 semiskilled jobs and 719 skilled jobs went unfilled, despite the fact that 874 unskilled, 532 semiskilled and 148 skilled Black applicants were available for employment.5

1955

Racial preferences in advertising becomes illegal under Michigan law, but more impactful were discriminatory actions of unions, workers and hiring managers against Blacks.5

1958

By this year, the construction of seven miles of the Lodge Freeway from downtown to Wyoming Avenue displaces 2,222 buildings compounding housing shortages, especially for Blacks. Part of a larger urban renewal effort Mayor Albert Cobo referred to as the “price of progress.”5

1962

President John F. Kennedy signs executive order banning discrimination in federally financed housing, but it only applies to new housing, not existing housing.5

1960s

Black Bottom and Paradise Valley, home to some of the city’s major strips of Black-owned businesses, social institutions and entertainment centers are razed in urban renewal program and replaced with Chrysler Freeway and Lafayette Park making it easier for commuters to reach auto plants being built in the suburbs. Many residents relocated to large public housing projects.4

1964

Civil Rights Act bans use of racial discrimination in housing, but is largely ignored.5

1968

Fair Housing Act outlaws housing discrimination and redlining. By then many African American families could no longer afford those houses as whites bought into suburbs accruing equity and wealth. Subsequent decades of local, state and federal policies continue to support de facto segregation.1

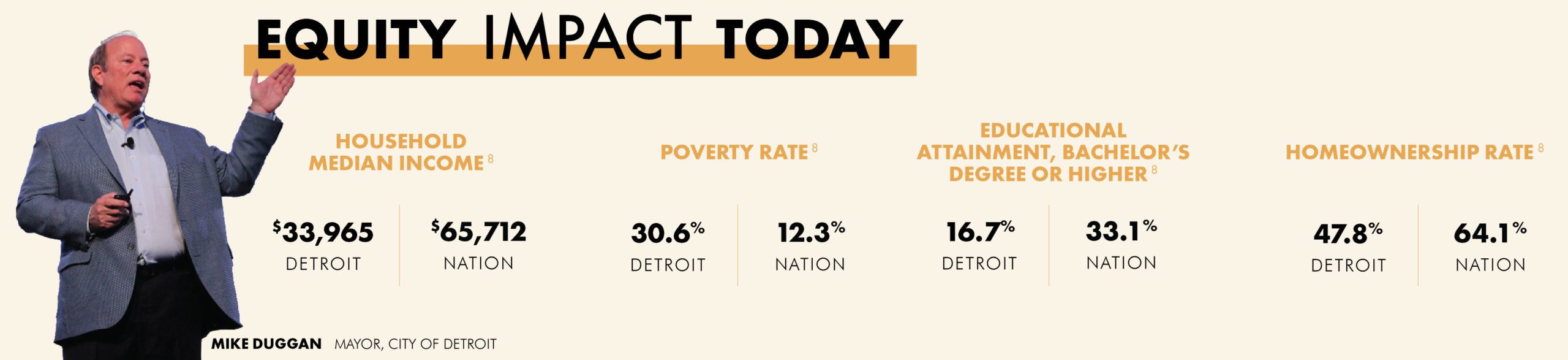

At the 2017 Mackinac Policy Conference, Mayor Mike Duggan highlighted the impact of the discriminatory policies which have led to poverty, home ownership, and educational attainment rates today in Detroit well below the national average with a disproportionate impact on Blacks. Such disparities better position whites to access good-paying jobs and to lean on generational wealth to weather and recover from crises such as the housing crash of 2008 and the subsequent foreclosure crisis and recession.

Sources:

- Center for American Progress

- VOX

- NPR

- Detroit Historical Society;

- “The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Racial Inequality in Postwar Detroit,” Thomas J. Sugrue, 2005; 6. PBS; 7. History.com 8. U.S. Census American Community Survey, 2019 One-Year Estimates.